Points to remember

- Mont Blanc offers a climatic journey from the Mediterranean to Greenland. This diversity of climates and therefore of unique natural environments makes it an exceptional place to study biodiversity.

- The pioneering scientists of Mont-Blanc made no mistake: it’s a unique open-air laboratory, and even more so in the current climate change context, where warming is more pronounced than in the Northern Hemisphere as a whole.

An open-air laboratory monitoring global changes

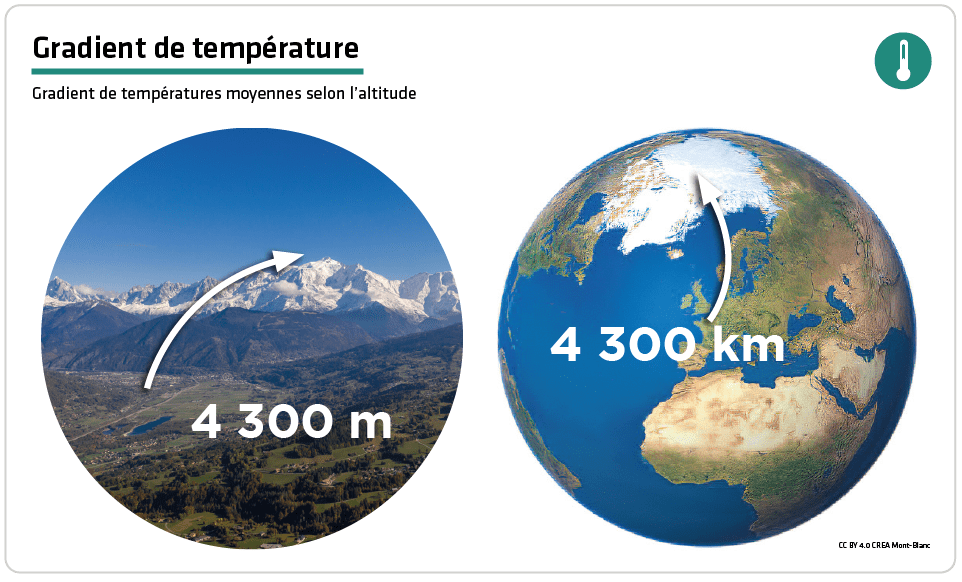

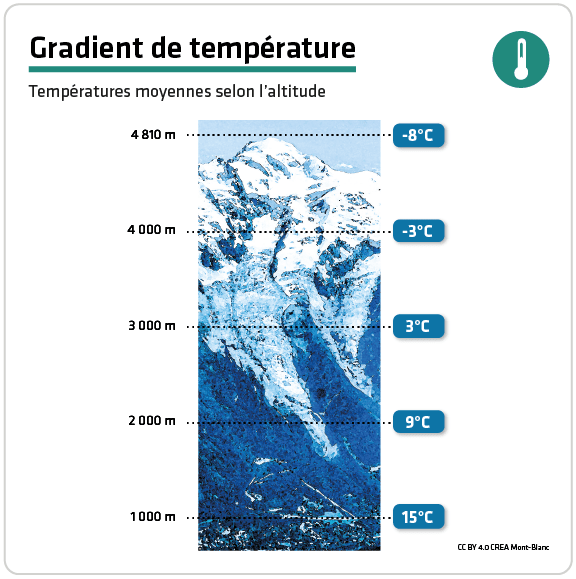

On average, the temperature decreases by 0.55°C for every 100 metres gained in altitude. This levelling – known to as the ‘gradient’ – of temperatures outlines the mountains: the temperature variations over short distances determine climatic conditions, ultimately leading to distinct ecological habitats for the plants and animals. The altitudinal distribution of vegetation closely mirrors that seen of the placing of vegetation in terms of latitude. Ascension in altitude and moving northward in latitude sees the progressive sequence of vegetation, starting with deciduous forest, followed by mixture forest, coniferous forests, heaths, toundra, rocks and then ice. Gaining 100 metres in altitude is roughly equivalent to traversing approximately 100 kilometres northward.

The Mont-Blanc massif boasts the largest altitudinal gradient in Europe (from 500m at Martigny in Switzerland and Le Fayet in France, to 4810m at the Mont Blanc summit). This very strong temperature gradient – the measure of temperature variation with altitude in °C/100m – gives rise to the unique result of microclimates, on a highly concentrated geographical scale, dependent on altitude and exposition. Ascending from the foot of certain valleys in Switzerland and Italy to the Mont Blanc summit, is akin to extensive travel across climatic conditions, from the Mediterranean to Greenland.

Gradual ascension in altitude therefore enough for researchers to observe the responses of the same species, either plant or animal, when living in different temperatures. This enables the study of a wide array of climatic conditions within a compact area, spanning the climatic gradients which prevail from southern Europe to the Arctic. As such, the Mont Blanc massif serves as an unparalleled research field for scientists investigating the reactions of fauna and flora to global climatic changes and seeking to forecast the evolution of landscapes. With the pace of climate change within the massif occurring at approximately twice the rate observed in the low-lying plains, the studies conducted here also offer valuable insight into the potential future conditions that other areas may face.

Geography of an extraordinary mountain

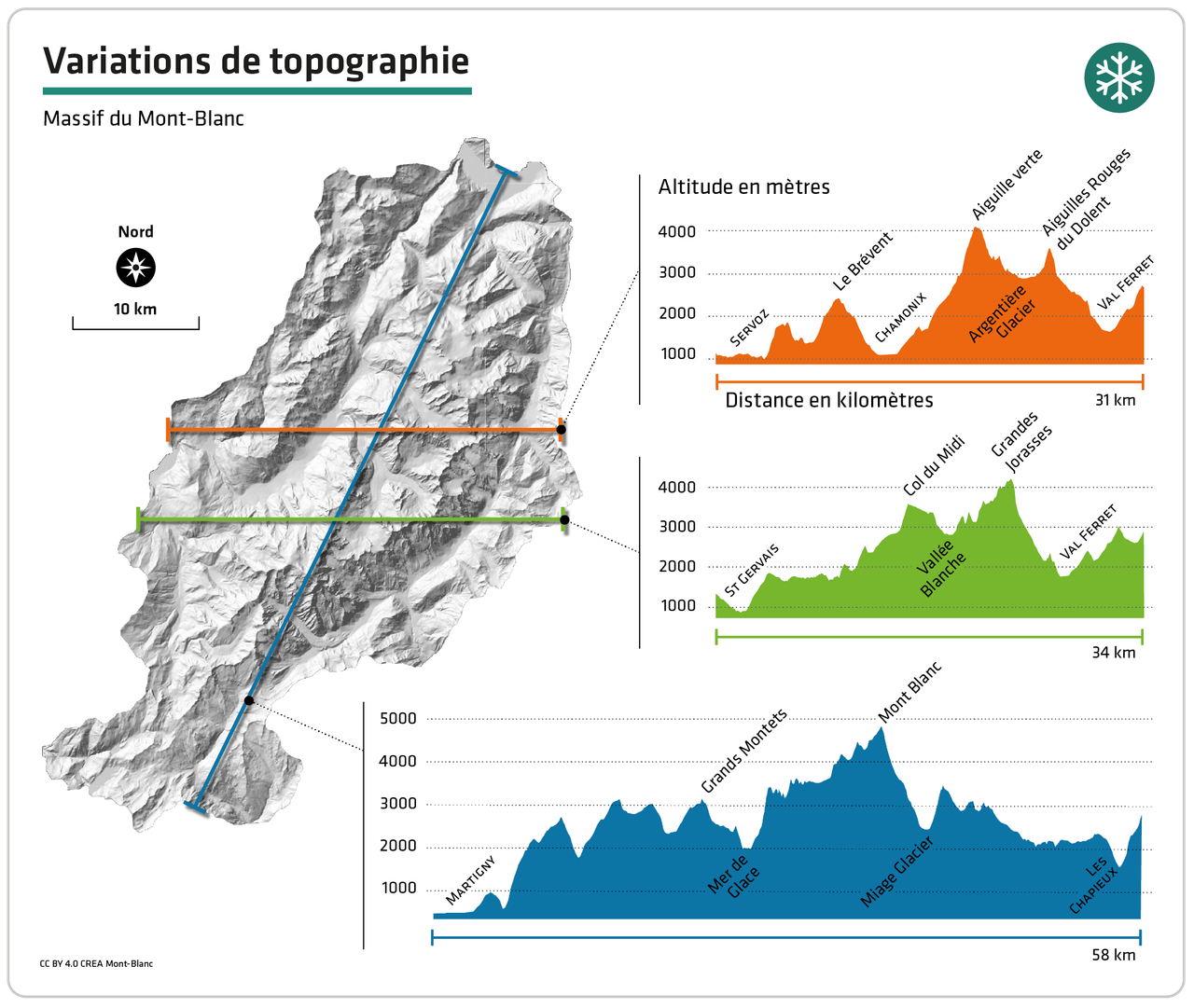

Mountain ecosystems are differentiated from other ecosystems by their topography, defined by altitude, slope, and orientation. With ascension in altitude, the temperature, atmospheric pressure, and humidity decrease, whilst at the same time solar ray intensity, wind power and duration of snow cover increase. The steepness of the slope and sun exposure may further impact these conditions. These topographical and climatic variations create both new possibilities of floral compositions and spatial distribution of species, presenting both opportunities and constrictive challenges for species inhabiting the areas observed. The local mountainous area gives rise to micro-habitats, exerting influence on the floral composition and development of plants. For example, crevices in a landscape retain the snow for longer periods, shortening the season favourable for growth (vegetation period). In the face of climate change, it is perhaps also this greatly diverse array of micro-habitats which offers opportunities for certain species to find relatively favourable climatic conditions, without the need to migrate over long distances.

The race to the summit certainly has its limits, even in Europe’s highest massif. The Mont Blanc massif is characterised by an impressive elevation gain (spanning 4,300 metres from its lowest to highest point), but also a relatively small surface area, stretching a mere 38km2. In other words, an altitude gradient of 4,300 metres is attained across a horizontal distance of approximately 20km. The steep incline of the Mont-Blanc massif, with its very abrupt slopes, means a significant reduction of surface area towards the summit. The surface area between 2,000 and 3,000 metres is comparatively twice as large as the area between 3,000 and 4,000 metres in altitude. For alpine species, the race to higher altitudes is therefore accompanied by a loss of suitable habitat on which to settle.

History: a passion for mountain science

The adventurous pioneers of alpine science made no mistake. Since the 18th century, Mont Blanc has attracted scientists wanting to validate hypotheses, develop new theories or test new tools in extreme conditions. Glaciologists, meteorologists, geographers and geologists have followed in their footsteps for several centuries, inventing mountaineering in the process to acquire to their research needs. Relatively little research has been carried out in ecology, hence the monitoring undertaken by CREA Mont-Blanc, encompassing the spirit of exploration of these early researchers.

Discover the scientific history of the Chamonix Mont-Blanc valley through the character of Joseph Vallot, brought to life by Aëlig Créno, an illustrator and graduate of the École Estienne in Paris.

Read online ➞Joseph Vallot has also been published by CREA Mont-Blanc Editions: a mountaineering scientist, naturalist and botanist, Joseph Vallot climbed Mont Blanc thirty-four times, breaking new ground in glaciology. A visionary, he understood from the outset that the Mont-Blanc massif could be an exceptional laboratory for Nature, and he devoted forty years of his life to the study of the high mountains.

Read or order the booklet Joseph Vallot ➞