Points to remember

- The longer the snow cover lasts, the better for the mountain hare and the worse for the brown hare, its direct competitor.

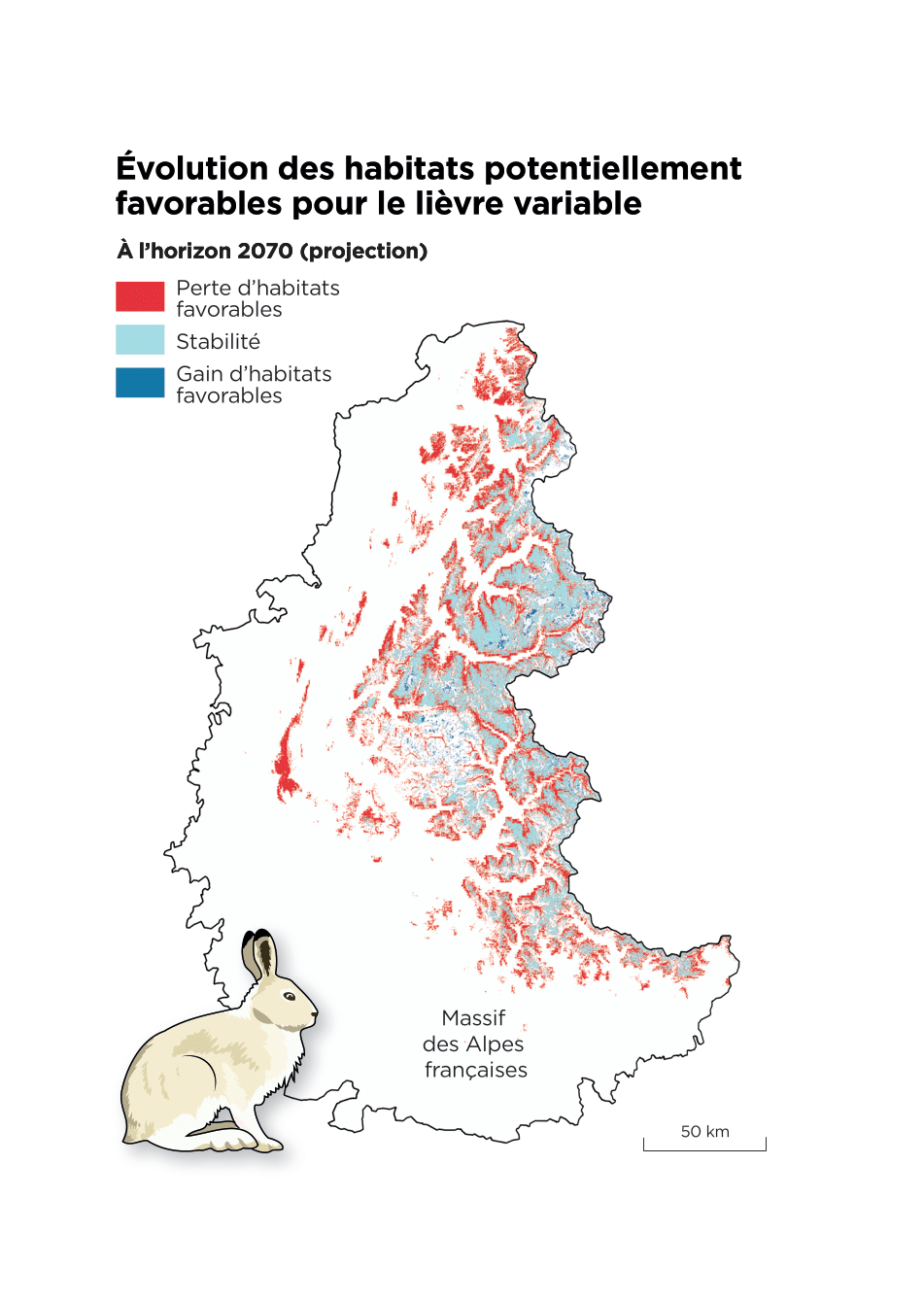

- Models projecting the future indicate a probable shrinkage of the areas occupied by white species towards higher altitudes.

- A better understanding of shy species, such as the mountain hare, is essential for implementing targeted and more effective conservation measures.

View indicator ➞

Issue: what happens to a white species in a world where the cold and snow are gradually disappearing?

The mountain hare is an emblematic high-altitude species. It is nicknamed the “white species” in reference to its winter coat which allows it to blend into the background and go unnoticed. In a rapidly changing world, this species is already a climate refugee on the summits of the Alps.

The mountain hare is a specialist of snowy terrains that has been moulded by its interactions with its habitat over a long evolutionary history. Its coat is particularly dense and effective at insulating it from the cold. Its ears are rather short (compared with its lowland cousins) and often folded back: the surface area exposed to heat loss is minimal. Finally, its stocky build, its ability not to move much and to wrap itself into a ball - minimising the surface area in contact with the air - help it to save energy.

Mountain hare under cover © Parc National des Écrins, Marc Corail

Predation by foxes, eagles or ermine is the main cause of death for the mountain hare. Its camouflage varies with the seasons: snow-white in winter, earthy brown in summer to merge into the background. The mountain hare becomes even more invisible when its movements are reduced in winter. Finally, its predominantly nocturnal activity patterns help it to keep a low profile.

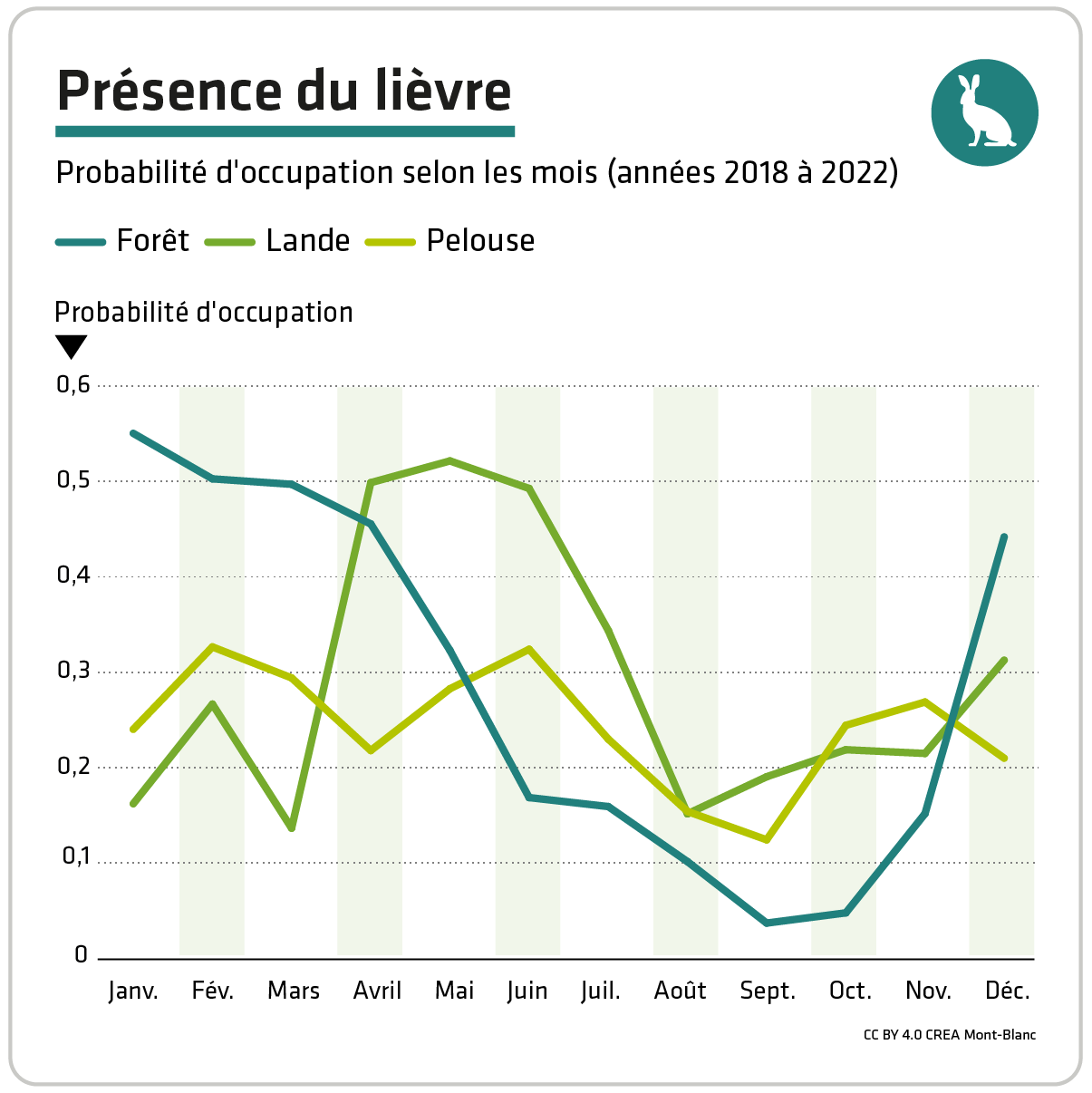

Relevance: the mountain hare’s use of its natural habitats

How does the mountain hare take advantage of the mosaic of natural habitats among forests, moors and grasslands? What are its activity patterns and how do they vary with the seasons? What is the link between seasonal variations in vegetation and the mountain hare’s activity? Can we observe a desynchronisation between their fur colour and changes in the snow cover?

The photo traps in the Mont Blanc massif show that the mountain hare is mobile on slopes and has a strategy for occupying the vegetation mosaic season-by-season, with one key theme: the possibility of hiding from predators in the vegetation and sheltering from the cold.

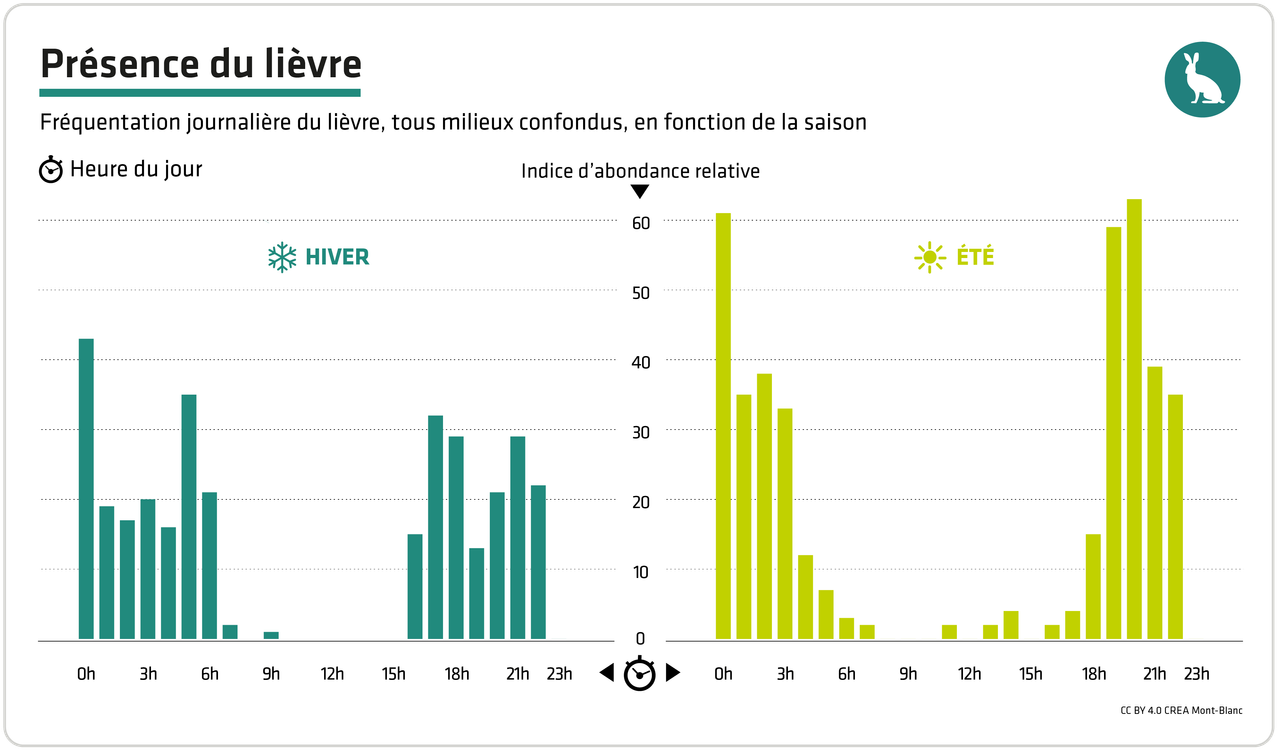

Over the course of twenty-four hours, mountain hares are more active at night than during the day. During the breeding season (April to August), there is a high peak of activity at sunset, then the hare remains active at night but at a lower rate, and its activity drops off about 2 hours before sunrise. During the winter period between October and February, activity falls from 6 a.m. (two-and-a-half hours before sunrise), then picks up again around 6 p.m. (one hour after sunset). The hare is active at dusk and during the night in summer and is nocturnal in winter.

Activity patterns of the mountain hare from April to August, and from October to February. The vertical lines indicate sunrise and sunset times in June (on the left) and December (on the right).

The mountain hare occupies various habitats throughout the year. It is generally found at an altitude of between 1,400 and 2,500 m. Its main winter habitat is forest (from December to April). It can reduce its energy expenditure linked to the cold by sheltering in this way and food can be found here in the form of buds or twigs.

In the spring and early summer (April until June), mountain hares migrate to higher altitudes. They then occupy moorland and mixed terrains of moorland and grassland (used less frequently, but throughout the year). These areas with varied vegetation provide them with food and allow concealment when breeding.

We can see that the mountain hares use a range of altitudes and environments which enable them to combine their responses to three challenges: protecting themselves from the cold, escaping predators and finding food. Mountain hares benefit from this mosaic of vegetation and avoid high moorland with lots of bushes. However, with the abandonment of farming as well as climate change, the vegetation is tending towards the latter type more uniformly, a change in habitat that is not favourable to the mountain hare.

Trends in the distribution of the mountain hare

During the last great ice age, which began around 115,000 years ago, glaciers covered a large part of our regions. Conditions were advantageous for white species throughout most of Europe. Then, when the climate gradually warmed up around 10,000 years ago, the glaciers steadily retreated. “Arctic-alpine species" such as the mountain hare found themselves “stranded” in the mountain ranges. They are still present in the Arctic.

Find out more about climate change in the mountains ➞With climate change, favourable conditions for the mountain hare are shifting to higher altitudes. Their populations are separated from each other, inhabiting “islands in the sky” that are likely to gradually shrink in size - a trend which could well reduce the number and size of populations.

We will probably see a desynchronisation between their moulting and the habitats, meaning more and more individuals in their white winter coats when the snow has not yet arrived or has already melted.

Future projection models indicate a probable contraction in the areas occupied by white species towards higher altitudes. This would mean the disappearance of mountain hare populations from the fringes of mountain ranges, the Pre-Alps and southern Alps. However, it is expected that the highest massifs (including Mont Blanc) will serve as refuges. Preserving these cold, high-altitude areas will therefore be crucial to maintaining the white species.

In the Alps, genetics has shown that seven populations can be identified and they display varying degrees of isolation from each other: there is little or no exchange of individuals between these groups. The smaller and more isolated the population, the greater the risk of extinction.

This picture painted by the most recent data confirms the mountain hare’s vulnerability in the face of climate change: less snow and higher temperatures may well allow the brown hare to climb up to higher altitudes, pushing the mountain hare into increasingly restricted areas at high altitudes.

Outlook: competition between hare and hare

In the Écrins a genetic analysis focussed on distinguishing between the mountain- and the brown-hare, confirming that they coexist at lower altitudes and, therefore, that this probably means competition for the mountain hare. Among the environmental parameters, the annual duration of snow cover is the best way of predicting the presence of the two species of hare. The longer the snow cover, the better the conditions for the mountain hare and the worse for the brown hare. In the Mercantour, we can see that there is currently little overlap between the population distribution of the two hare species. By repeating this type of tracking over time, we will be able to see whether the areas favourable to the mountain hare are shifting up to higher altitudes and whether there is an increasing overlap between the areas occupied by brown hares and mountain hares… Interbreeding between the two species has been observed in genetic tests but is still rare at present.

Competition between the mountain hare and brown hare has also been confirmed by photo traps and this video recording of a fight.

Several unknowns remain. To what extent will these species be able to adapt to changes in their environment? Will they take advantage of the “micro-refuges” which mountains can offer so as to maintain their presence at intermediate altitudes? What will be the consequences of glacier retreat which might free up potential habitats?

References

Sur les traces du lagopède alpin et du lièvre variable, CREA Mont-Blanc Éditions

Rédaction : Francine Brondex / Le fil conducteur,

Anne Delestrade, Irène Alvarez (CREA Mont-Blanc),

Jérôme Mansons (Parc national du Mercantour),

Charlotte Perrot (OFB), Yoann Bunz, Pierre Bouvet

(Parc national des Écrins).

Infographies : Iris de Véricourt.

Le lièvre variable : comment suivre une espèce aussi discrète.

Ludovic Imberdis & al. Faune sauvage n°320, 2018.

Suivi des changements de distribution hivernale du lièvre variable (Lepus timidus) et du lièvre d’Europe (Lepus europaeus) sur leur zone de contact dans les Alpes françaises. Thibaut Couturier & al. Rapport d’étude programme POIA Espèces arctico-alpines, 2021.

Modélisation des habitats favorables au lagopède alpin (Lagopus muta) et au lièvre variable (Lepus timidus) dans les Alpes françaises. Maya Guéguen & al. Rapport d’étude programme POIA Espèces arctico-alpines, 2022.

Étude des facteurs paysagers affectant les flux de gènes chez le Lièvre variable. Salomé DOVAL & al. Rapport d’étude programme POIA Espèces arctico-alpines, 2022.

Déplacements altitudinaux et rythme d’activité du lièvre variable d’après les données de pièges photos, Marjorie Bison & al. Rapport d’étude du programme POIA Espèces arctico-alpines, 2022.

Partners