Points to remember

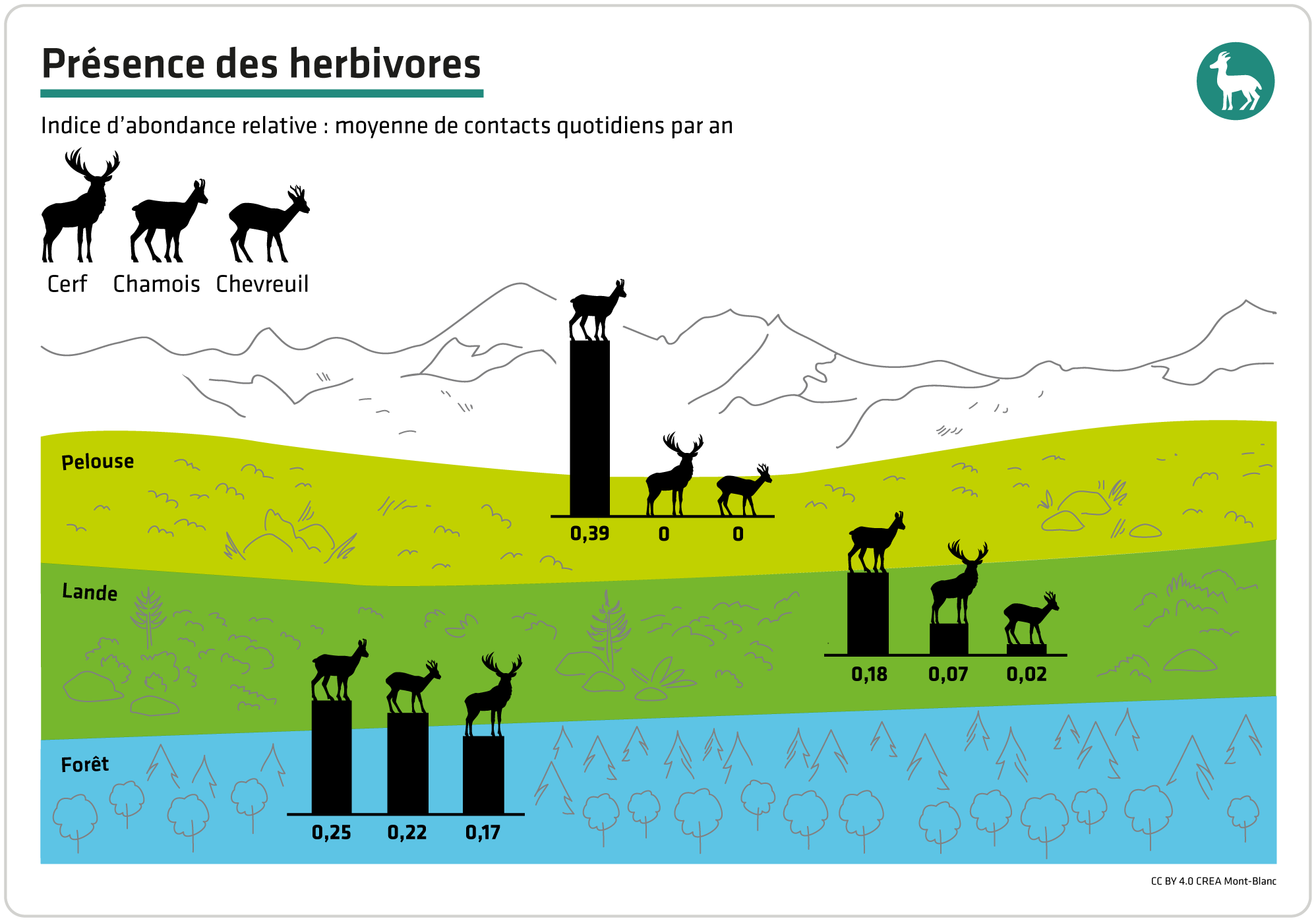

- Large herbivores (chamois, red deer, roe deer, ibex) use different natural environments in the massif (forest, moorland, grassland) in a species-specific way and according to the season.

- Little has been known so far about their use of different areas in the massif, hence the creation of a photo-trap network. This enables cross-referencing of the species’ occurrence in various habitats with data about vegetation and temperature.

- The network will allow a better understanding of how large herbivores’ distribution and numbers develop as the climate changes. It will also shed light on their use of the different habitats, particularly moorland.

View indicator ➞

Issue: Mont Blanc as an area grazed by…wild herbivores

The most commonly-found large herbivores in the massif are chamois, ibex, red deer and roe deer. Two (partly linked) characteristics of Mont Blanc are: a less “domestic” pastoralism compared to other massifs plus the prevalence of moorland, an environment which is less suited to herbivore grazing than grassland. This is, therefore, a very interesting context to observe the “browsing pressure” caused by wild herbivores on natural habitats and how the latter are used by these species.

These large herbivores are all ungulates (they walk on their hooves). Their diet varies according to the species, being more selective for roe deer or chamois, for instance. They feed on herbaceous plants, leaves and semi-woody or woody matter (buds, twigs, young shoots), especially in winter. In the Mont Blanc massif, as in the rest of France, populations of large wild herbivores have been increasing for the last thirty years (source: OFB). Alongside this, forest expansion also furthers the development of woodland herbivores (particularly roe deer and red deer).

Numerous studies have focussed on the interactions between large herbivores and how these affect their population dynamics. In 0most cases, researchers do this by comparing populations in the presence or absence of another species. In the Bauges massif, for example, the presence of mouflon does not affect the chamois’ activity patterns, habitat selection or food niche when they live together in the same areas (‘sympatry’). In contrast, the quality of chamois’ diet decreases when a high density of deer is present, thus contributing to a fall in winter survival rates among young chamois.

Pertinence: The relevance of herbivores’ use of the slopes

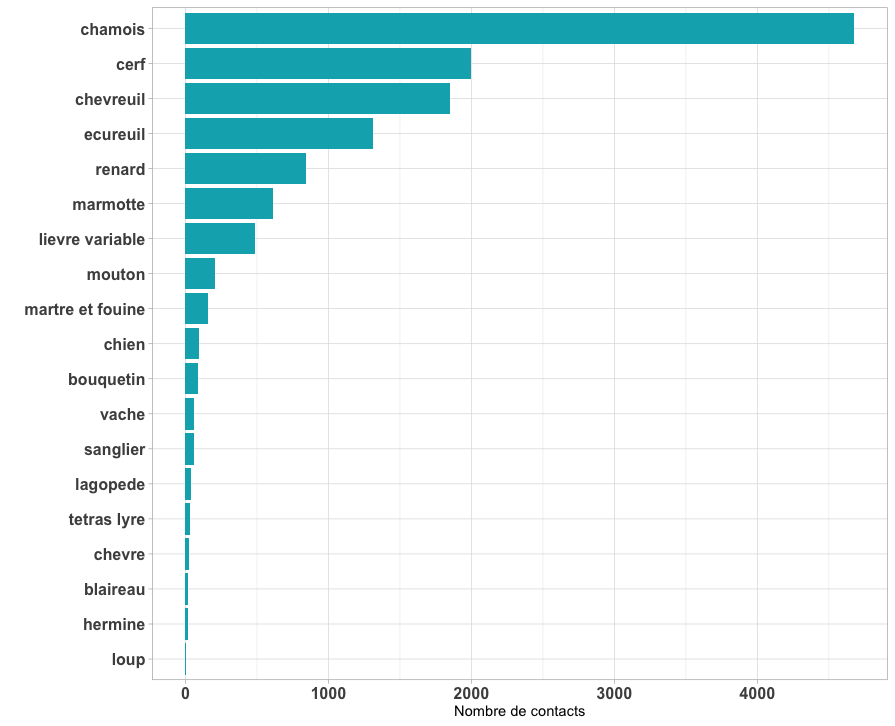

Frequency of different species detected by the photo-trap network of CREA Mont-Blanc (2018-2020)

A characteristic of mountain areas is the rapid variation in altitude and, therefore, the juxtaposition of different natural environments over short distances. Forests, moorland and alpine grassland give way to each other in succession. Herbivores know how to gain benefit from each habitat, chamois being found in all these areas, deer in the forest and on moorland, with roe deer mainly in forests. There has been little study of how these species use these different environments around Mont Blanc so a network of automatic photo traps has been set up.

Around forty photo traps have been set at every 200 metres of height gain on the slopes of the massif. They are automatically triggered when an animal passes by, thus making it possible to monitor how often these different habitats are used by the herbivores. Since most of the photo traps were installed in 2018, we so far only have a season-by-season inventory of occurrence by altitude and activity pattern for the targeted species (chamois, roe deer, red deer). The long-term time trends will follow in a few years. The number of animals can be estimated in several ways: by counting different direct sightings or via the photo traps, by faeces counts or other traces, by capture-mark-recapture methods which identify and track individual animals (rings, GPS). The photo trap technique allows more consistency in observation, regardless of the time or weather conditions. However, none of these methods can determine the exact size of a population. But they are useful for comparing the different areas sampled while using the same procedures or for studying how animal densities develop over several years.

Large herbivores - chamois, red deer and roe deer - are detected most as they are the most abundant and/or the most easily picked up by the photo traps. This method is appropriate for studying their distribution over the slopes, the areas they occupy season-by-season and, given time, how their numbers develop.

The space that animals use in the “gradient” of altitude and habitat provided by a slope depends on resource availability, especially food, and by social relations in the group, for example when reproducing or rearing their young. The gradient structure of the mountains enables animals to change environment rapidly in order to find other resources.

The probabilities of large herbivores’ occurrence in the various habitats are in line with what we expected: red deer in forests and on moorland with roe deer mainly in forests. Chamois are spread over the three environments: greater or lesser probabilities of finding them in each habitat depend on the season (in forests during spring, then on moorland and mostly on grassland in the autumn). Roe deer and red deer have never been caught on camera above 2200 metres.

Moorland is ‘a priori’ a less favourable environment for certain species. Resources here are less diverse, often woody (rhododendrons, juniper..) and not very appetising; the high, dense vegetation makes movement more difficult. The three species studied are observed there. But it is not yet certain whether they just cross this area or if they actually feed there. Initial analysis shows that red deer are often found there, sometimes higher up than expected. It is known that grazing and browsing by red deer in other habitats can create a lot of pressure and completely change the environment. While moorland is characteristic of Mont Blanc and an issue in land management, the impact and abundance of red deer in this environment is a key factor requiring analysis in the coming years.

Evolution: Changes in herbivores’ activity according to the season

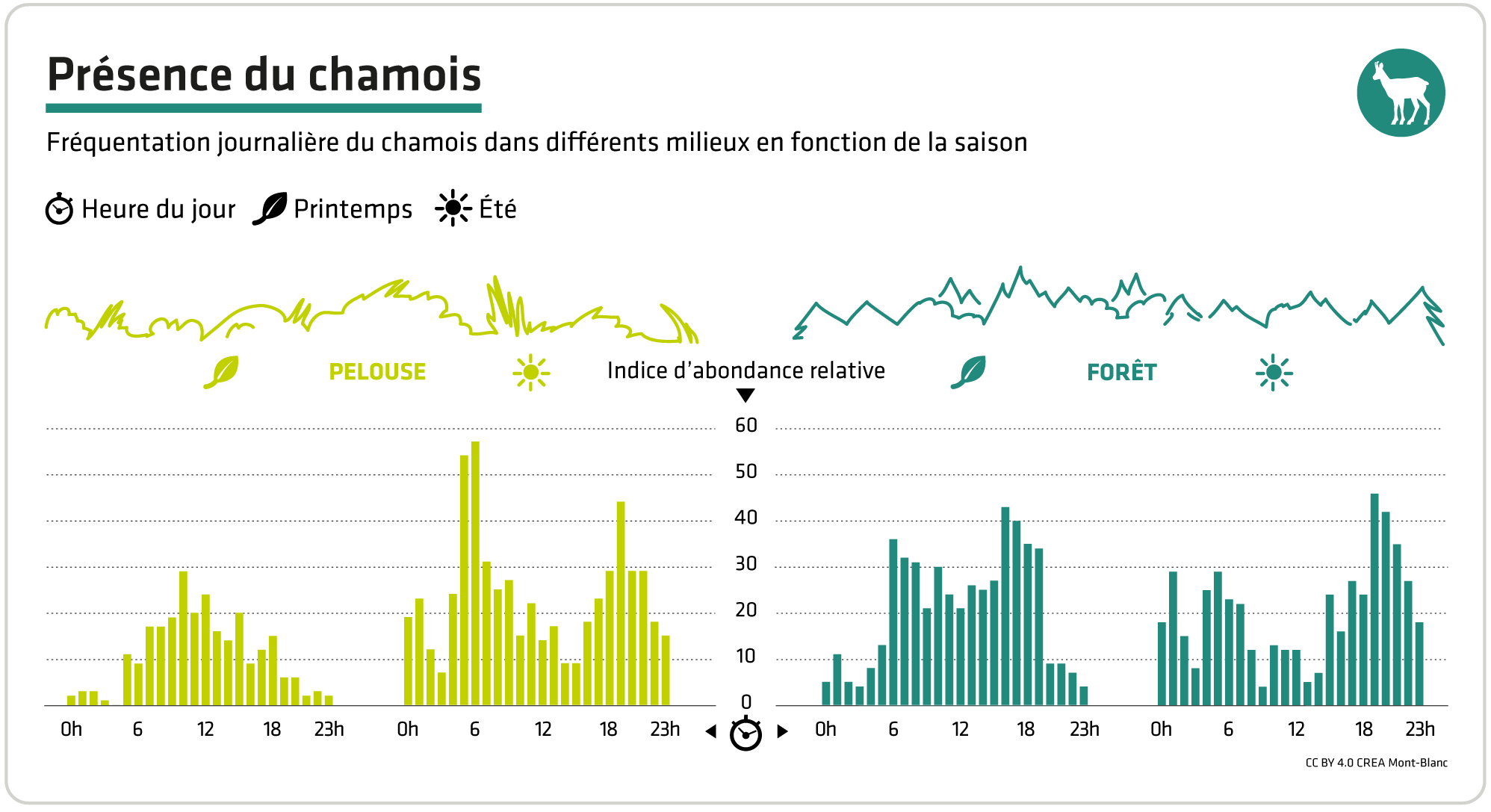

Large herbivores are relatively sedentary but they adapt their daily rhythms and how often they use different habitats according to the season. The example of the chamois shows an increased presence on grassland during the summer and in forests in winter, sometimes at low altitude. Similarly, its daytime activity in winter is very different to the summer and sometimes even includes nocturnal activity.

The activity patterns vary from one season to another and the observations made around Mont Blanc are in keeping with the results in scientific literature. All three species display strong bimodal activity in summer with peaks around 6am and at about 7pm. In the case of chamois, we observe a single activity peak in winter at the warmest time of day. Likewise, the activity of the two other species (roe deer, red deer) increases in the middle of day during winter, although they still keep their two activity peaks at the beginning and end of the day.

As for the chamois, there are behavioural differences between forest and grassland chamois in autumn and spring. Since the grasslands are at a higher altitude, spring temperatures there are colder than in the forest, thus suggesting the same behaviour as in the winter forest with an activity peak in the middle of the day. However, this should be investigated in more detail. Similarly, the chamois is a diurnal animal. But we sometimes observe from the photo traps a nocturnal activity peak, depending on the season: little was known about this until now.

One of the final objectives of this study is, therefore, to link the probability of occurrence to the phenology of a particular habitat (snow cover, vegetation productivity) and to climate, in order to gain a more precise understanding of how the species optimise the available resources along the slopes according to the season.

Perspectives: Development prospects of herbivores in the long-term

Young ibex

Enhanced knowledge about occurrences in herbivore areas, categorised by altitude and season, will eventually allow cross-referencing of these readings with climate and vegetation data. The latter is changing as the climate changes, both in terms of composition - forest and moorland development - and of seasonality: an increasingly early start and peak of plant productivity. The question for study about the future of herbivores is, therefore, whether they will remain “synchronised” with their environment.

A “desynchronisation” has already been observed, especially with ibex and chamois, between the breeding cycle of the young and plant productivity. The young need tender and particularly nutritious grass during weaning. However, the date of calving varies little with these mammals, even though vegetation is appearing earlier and earlier. This mismatch between the herbivores’ breeding season and the emergence of vegetation leads to sub-optimal growth among the young plus higher mortality the following winter. If herbivores cannot easily adapt their “timing”, perhaps they can adapt spatially by moving towards better resources? Or on the other hand, could the tendency of vegetation growth towards more moorland and forest add a space restriction to the time constraint which we already know about?

There are still only a few studies of mountain areas that focus on the slopes. And yet herbivores are particularly mobile and dependent on snow-free areas and vegetation. The photo trap approach, including a volunteer platform to identify the animals photographed (the Wild Mont Blanc platform), will make it possible to link these spatial and time perspectives and provide a better understanding of the Mont Blanc herbivores’ population dynamics.

References

- Brivio F., Bertolucci C., Tettamanti F., et al. (2016). The weather dictates the rythms: Alpine chamois activity is well adapted to ecological conditions Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 1291–1304. 10.1007/s00265-016-2137-8

- Darmon G., Bourgoin G., Marchand P. (2014). Do ecologically close species shift their daily activities when in sympatry? A test on chamois in the presence of mouflon Biological Journal of the Linnean Society . 10.1111/bij.12228

- Mason T., Stephens P. Apollonio M. et al. (2014). Predicting potential responses to future climate in an alpine ungulate: interspecific interactions exceed climate effects Global change biology 10.1111/gcb.12641

- Sprem N., Zanella D. Ugarkovic D. et al. (2015). Unimodal activity pattern in forest-dwelling chamois: typical behaviour or interspecific avoidance ? European Journal of Wildlife Research 10.1007/s10344-015-0939-z